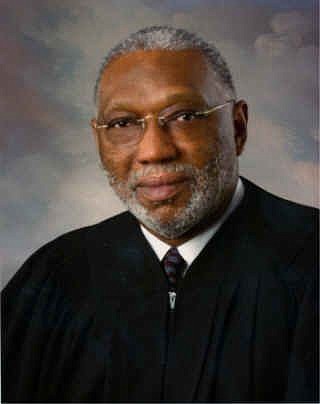

In what might have been his last word on the issue as a member of the Florida Supreme Court, Justice James E.C. Perry last week rendered a blistering analysis of the manner in which the death penalty is carried out in Florida.

Perry’s 10-page dissent in the case of Mark James Asay came eight days before his constitutionally mandated retirement from the court on Friday.

The Columbia Law School graduate referred to his pending departure in the dissent in a highly anticipated decision about the application of a seminal U.S. Supreme Court ruling this year in a case known as Hurst v. Florida.

The Hurst decision, premised on a 2002 ruling in a case known as Ring v. Arizona, found Florida’s system of allowing judges, instead of juries, to find the facts necessary to impose the death penalty was an unconstitutional violation of the Sixth Amendment right to trial by jury.

The Florida court on Thursday decided the Hurst ruling should apply to all cases that were finalized after the 2002 Ring opinion — but not to cases, such as Asay’s, that were finalized before Ring.

The effect will be that death row inmates sentenced after Ring will be able to seek new sentencing hearings while those in earlier cases, like Asay, will not.

But, in a blistering condemnation of the death penalty in general, Perry disagreed, calling the majority’s decision “arbitrary” and one which “cannot withstand scrutiny under the Eighth Amendment” because it creates two groups of similarly situated persons.

“Coupled with Florida’s troubled history in applying the death penalty in a discriminatory manner, I believe that such an application is unconstitutional,” wrote Perry.

In a footnote, Perry, who is black, wrote he is “aware of the irony” of discussing discrimination in the context of the case of Asay, who would be the first white person to be executed for killing a black victim in Florida.

“It does not escape me that Mark Asay is a terrible bigot whose hate crimes are some of the most deplorable this state has seen in recent history,” Perry wrote.

“However, it is my sworn duty to uphold the Constitution of this state and of these United States and not to ensure retribution against those whose crimes I find personally offensive,” he continued.

More than 70 percent of Florida prisoners who have been executed were black men whose victims were white, Perry wrote.

“This sad statistic is a reflection of the bitter reality that the death penalty is applied in a biased and discriminatory fashion, even today,” he wrote.

Because of his impending retirement, Perry wrote he felt “compelled to follow other justices who, in the twilight of their judicial careers, determined to no longer ‘tinker with the machinery of death.’ “

Thursday’s majority decision not to apply the Hurst decision to all of the nearly 400 inmates on death row “leads me to declare that I no longer believe that there is a method of which the state can avail itself to impose the death penalty in a constitutional manner,” Perry wrote, adding he would find the Hurst ruling “applies retroactively, period.”

Perry pointed out the Florida Supreme Court took a different approach to a U.S. Supreme Court decision that found life sentences for juveniles violated Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. Florida justices said that decision should apply retroactively.

In contrast, the majority on Thursday “decides that in capital cases where the Sixth Amendment rights of hundreds of persons were violated, it is appropriate to arbitrarily draw a line between June 23 and June 24, 2002 — the day before and the day after Ring was decided,” Perry wrote.

The majority opinion treats 173 inmates whose sentences were final prior to Ring differently from the others on death row, which Perry said was unconstitutional.

The majority, in part, objected that requiring resentencing for all of the state’s 386 death row inmates would create a substantial burden on the judicial system.

But Perry wrote the court could easily resolve the situation by vacating all of the death sentences and imposing life in prison without parole, something he has repeatedly insisted Florida law requires if the state’s death penalty has been found unconstitutional.

“In other words, this court has rejected an available remedy that creates no burden but then pronounces that the burden is far too great to provide equal application to similarly situated defendants,” he wrote.

Defendants who committed offenses at an earlier date but had their sentences vacated and were later resentenced will now be eligible for resentencing again, Perry wrote.

“The majority’s application of Hurst v. Florida makes constitutional protection depend on little more than a roll of the dice. This cannot be tolerated,” he wrote.

Perry, appointed in 2009 by former Gov. Charlie Crist, is among five jurists who make up a liberal-leaning majority of the seven-member court, which has drawn the wrath of the Republican governor and the GOP-dominated Legislature.

Other members of that bloc are Chief Justice Jorge Labarga and justices Barbara Pariente, R. Fred Lewis and Peggy Quince.

Perry, 72, is forced to leave the court because the state constitution requires justices to retire when they turn 70. The law also allows justices like Perry to fulfill the remainder of their terms, depending on when their birthdays fall.