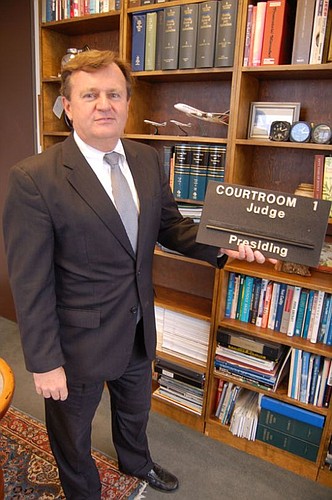

Monday-Friday, Ed Booth, a partner at Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, practices law.

In his spare time, if the board-certified aviation attorney and private pilot isn’t in the cockpit, he’s probably helping to preserve Jacksonville’s heritage, including the city’s historic architecture.

“I know we can’t save everything, but we’ve lost a lot,” said Booth, the immediate past president of the Jacksonville Historical Society.

The municipal code allows a building to qualify for designation as a local historic landmark when it’s been standing for 50 years. Since 2005, Booth has maintained what he calls his “endangered building list.”

Many of the city’s most historic buildings were demolished years ago as part of urban renewal, but Booth said there have been some notable rescues in terms of preservation and re-use.

“The No. 1 success story in terms of historic preservation in Jacksonville would have to be the Florida Theatre,” he said.

It opened in 1927 and marked its 90th anniversary April 8 by inviting the public to watch a silent movie and a documentary about the building’s history.

Other success stories include the transformation of the former Duval High School into the Stevens-Duval apartments for seniors Downtown on Ocean Street, the current renovation of the former First Guaranty Bank & Trust building at Bay and Ocean streets into the Cowford Chophouse and the ongoing preservation of the steam locomotive at the Prime Osborn Convention Center, Booth said.

Other preservation milestones are the conversion of the former John Gorrie Junior High School in Riverside into condominiums and adapting the former U.S. Post Office and federal courthouse West Monroe Street into the State Attorney’s Office.

Also on Booth’s success list is the Seminole Club, now home to Sweet Pete’s candy factory and retail store and the Candy Apple Café.

He admits there have been attempts at preservation that fizzled, most notably two structures in LaVilla.

One is Genovar’s Hall, a former nightclub that was a hot spot in the early 20th century when Jacksonville was known as “Harlem of the South.” The jazz greats of the day, including Louie Armstrong and Billie Holliday performed there, but it’s been fenced off for years.

The other is Brewster Hospital, Booth said. The city owns and has preserved what was at one time the only hospital in Jacksonville for African-Americans, but it sits empty.

“The city lovingly restored it, but there’s really no use for it,” said Booth.

Buildings at the top the current endangered list are the Ford Motor Co. assembly plant at the west end of the Mathews Bridge and the former Ambassador Hotel Downtown near the Duval County Courthouse.

There’s also a mystery in Jacksonville’s history — not about the event, but about why there is so little record of it. It’s also related to Booth’s interest in aviation and it has put him on a quest.

Booth said when Charles Lindbergh flew to Jacksonville in October 1927 on his nationwide tour, five months after he became the first to fly an airplane across the Atlantic Ocean, more than 150,000 people came here to see the famous aviator and his “Spirit of St. Louis” that flew from Long Island, N.Y. to Paris.

The mystery is that there are only five photographs of the event in the historic archives.

“I know somebody took pictures. They’ve got to be sitting in an attic somewhere,” Booth said. “My personal mission is to find more pictures of Lindbergh’s visit.”

(904) 356-2466