On one night in February 1976, Earl Benton held the keys to life as the world knew it.

At 180 feet down a missile silo in Little Rock, Arkansas, the U.S. Air Force captain, at the age of 25, was awaiting instructions.

“We were teetering on the brink of war,” recalls Benton, 68.

“The keys were out of the safe,” he said. “We had top-secret authenticated messages and we were sitting there ready to go.”

Deep thinking filled the time. “Bad things have to be happening in other parts of the world. We wondered what’s going on. You wonder if you’ll ever see the sun shine again.”

The crew waited.

“Our keys were inserted and we awaited the launch codes for around 20 minutes before we were ordered to return them to the safe,” he said.

“I still have nightmares about that night.”

The crews on alert earned two weeks off. Some didn’t return to that program.

Benton did. “Oh yeah,” he said. “I went back.”

From the silo to a career

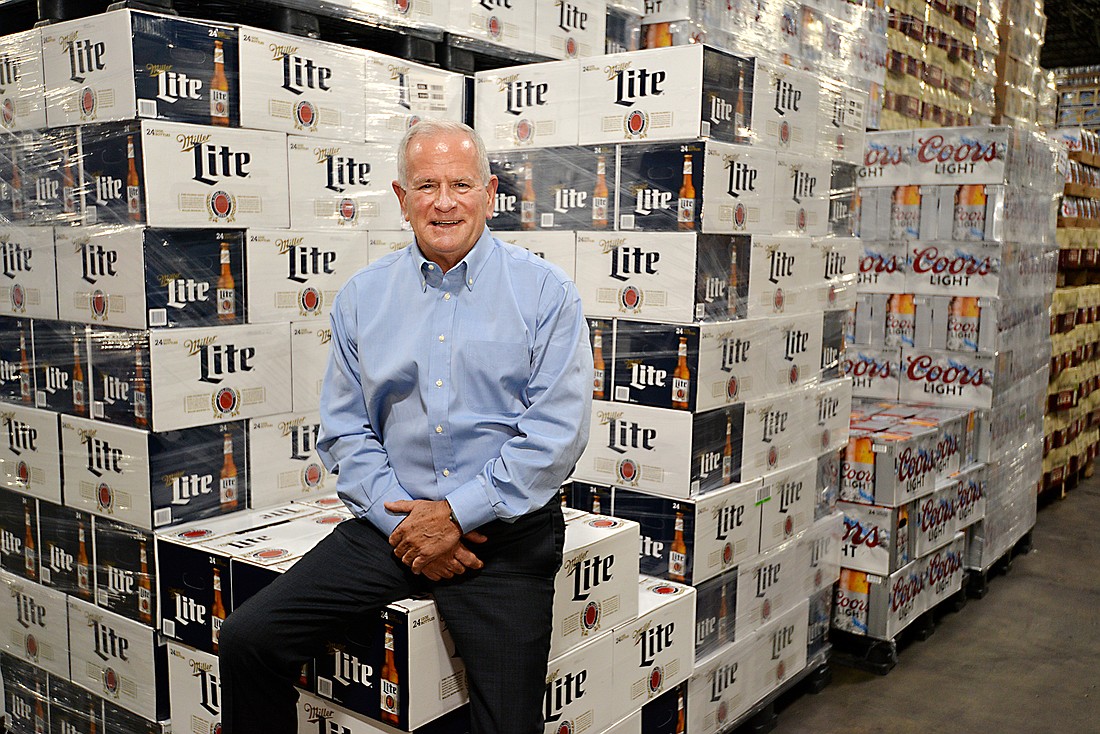

Benton completed his four years in the Air Force and returned to the private sector, a path that led him to buy a beer distributorship in Jacksonville and grow it as Champion Brands Inc. He’s president and CEO.

Benton was born and raised in rural North Carolina on a tobacco farm.

“I spent 22 wonderful summers there. And I knew one thing I didn’t want to be when I grew up was a tobacco farmer.”

He earned an Air Force ROTC scholarship in high school and spent four years at East Carolina University, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in accounting in 1973.

Off he went to pilot training, but astigmatism in his left eye meant that instead of flying a fighter plane, he was trained for the missile silo.

He exited the Air Force into a slow economy. Not finding a job, he enrolled in graduate school at the University of Arkansas for an MBA.

The economy improved during that time.

A friend took a job with Miller Brewing Co. and suggested Benton apply. A nice form letter told him Miller wasn’t hiring but would keep his resume on file.

He answered a newspaper ad to work at Union Carbide, making about $8,800 a year compared with $14,000 as an Air Force captain.

Along with the salary came a company car. “When I got it, it had 200,000 miles on it. And it smelled like it had been a dog kennel in the back,” he said, figuring its last driver traveled with his pet.

Union Carbide moved Benton to Oklahoma City, where he covered Oklahoma and Kansas. About two months later, Miller came calling.

“I gave Union Carbide 30 days’ notice and I’ve been in the beer business ever since.”

‘Never heard of Jacksonville’

Benton worked for Miller Brewing Co. about six years when he bought a small distributorship in Jackson, Tennessee.

Two years later, the chief marketing officer, a friend he had worked with at the brewery asked him to check out a company in Jacksonville.

“That’s fine, but I’m really happy here,” Benton replied. Tennessee reminded him of North Carolina.

“You owe me,” said the friend, Leonard Goldstein. “The company is not doing well and we’d like to see if this wouldn’t be a fit for you.”

Benton agreed, asking by the way, where is this company?

Jacksonville.

“This is 1982 and I said, Leonard, I’ve never heard of Jacksonville, Florida, and I really hadn’t,” Benton said.

He asked Goldstein to find someone else. Goldstein, who later became chairman, president and CEO of Miller Brewing, wasn’t having it.

“Long story short, I made a weekend trip that following weekend because he’d already set it up, he knew he was going to make me go,” Benton said.

He brought clothes for a weekend but stayed for two weeks.

“I just kind of fell in love with the city, and this was in 1984. It wasn’t nearly what is today, but I could see green sprouts everywhere,” he said.

Calling it “a whale of an opportunity,” Benton bought Duval Beverage Distributors in February 1985.

From $10 million to $160 million in sales

That first year, there were 49 employees and sales were $10 million “and falling.”

Upon buying the company, Benton brought in a team from Tennessee to assess its management. “Once we got a handle on it, it turned around quickly,” he said.

Benton moved the company in 1988 from Northwest Jacksonville to Florida Mining Boulevard South in Mandarin, where it built a warehouse – the first of several expansions.

He changed the name to Champion Brands Inc.

The move brought Champion Brands closer to the center of its territory and limited the tolls, soon eliminated in 1989, delivery trucks had to pay as they crossed the St. Johns River.

Then came the three critical years.

In 1999, Duval Beverage Distributors carried only Miller products.

That year and the following, 2000, Benton bought the two area Coors distributors.

In 2001, Red Bull chose Champion Brands to distribute its energy drinks in Northeast Florida.

Champion Brands grew from selling 68 cases of Red Bull the first month and is on track to sell more than a million cases this year.

Benton built an office-warehouse complex at its Mandarin property at 5571 Florida Mining Blvd. S. and bought 6 acres in 2004 across the street at 5520 Florida Mining Blvd. S.

Champion Brands built a 36,000-square-foot, $7 million, energy-efficient office headquarters there, celebrating the grand opening last week.

Over 34 years, he and his team have grown the company to 319 employees and more than $160 million in sales and 6.1 million cases of beverages a year.

Champion Brands represents 62 domestic and international breweries, local craft brewers, water and nonalcoholic drinks in six Northeast Florida counties. The number of brands tops 300.

It holds more than a 40% market share in distributing malt beverages in its six-county Northeast Florida market.

Brands include Miller Lite, Samuel Adams, Yuengling, Heineken, Newcastle, Mike’s Hard Lemonade, Smirnoff Ice and White Claw Hard Seltzer.

Jacksonville brands include Intuition Ale Works, Veterans United Craft Brewery and Carve Craft Vodka, among others.

Champion Brands set up a Savannah, Georgia, office in 2006 to distribute Red Bull in 31 Southeast Georgia counties. The brand is so important that Benton assigned a wing of the new Jacksonville building for the brand’s business.

2 a.m. delivery rides

Benton’s team includes his son, Jacob, 32, general manager and his designated successor.

Jacob Benton worked with his father on and off since the age of 8, including mopping floors and riding routes. He worked with the architect to design the new building. He is a millennial, the workforce age group that Earl Benton knows needs to be cultivated.

Amenities at the new HQ include a taproom and bar that serves a large meeting room and an expansive outdoor patio; a 24/7 gym available to employees; rooftop solar; a dining and vending area; air and light sensors; and other elements.

In 2015, Champion brands opened the first public compressed natural gas station in Jacksonville and began converting its fleet to CNG trucks. The station is open to the public.

“We’d like to think that this is going to bring a quality of life that’s going to help us keep people. It’s people today that are your biggest asset,” Earl Benton said.

Benton’s management style is “walking around.”

“You never know where I’ll show up in the warehouse,” he said.

On Memorial Day 2017, he climbed on a delivery truck at 2 a.m. and rode with the driver. “Word kind of spread through the company. Very quickly.”

He also empowers. He doesn’t micromanage but said he’s quick to critique.

“We like to have fun, and we find at the end of the day, people are more likely to stay with you and work harder and longer and smarter if they like where they’re working.”

On that, the top management unit of about 30 people is in sync, he said.

Benton has no plans to retire. He enjoys his job, which he considers more of a paid hobby.

Jacob Benton says his father’s leadership style is one of presence and connection.

“He leads by example and his relationships with our team members at all levels allows him to gain insights that other senior leaders may miss,” he said.

“In addition to being our CEO, my Dad is passionate about numbers and wears his ‘CFO’ hat a lot,” he said. “His financial expertise has contributed greatly to our ability to grow.”

Jacob Benton also said his father is humble. “I think his background and upbringing have a lot to do with that.”

Ray Driver, a partner with the Driver, McAfee, Hawthorne & Diebenow law firm, knows Benton in several roles.

The two are members of the Rotary Club of Deerwood, and Driver chairs JAXUSA Partnership, the economic development division of JAX Chamber.

“Earl’s and Champion Brands’ continued investment of dollars into the business has been hugely impactful on numerous people in our community, including Champion Brand’s own employees and the employees of the companies that make up their supply chain,” Driver said.

Driver said Champion Brands’ investment into the new headquarters shows a long-term commitment to the area.

The company also is a strong philanthropic partner of many organizations, Driver said, donating money and products.

“They are a testament to what vision and leadership can do, and we are extremely fortunate to have them here.”

It wasn’t a test

Benton said that 43 years since the missile event, he still avoids small spaces because they remind him of the confinement in the silo.

After that night, Benton learned what happened the next day as the crew was taken by helicopter back to the base.

“They took us to a debriefing area and told us, ‘Guys, this wasn’t a test last night. B-52 bombers were taking off. You guys were sitting there ready to go, and it wasn’t a test. We wouldn’t put anybody through that,’” he said.

The trigger came from a test launch by the Russians, who simultaneously launched four missiles. Satellites picked up the flashes coming from their silos.

“It later turned out to be they were seeing just how much we could see,” he said. “It turned out just to be a reconnaissance kind of thing for them.”

Benton trained about a year to be a missile launch officer, and that night brought reality into focus.

“You think back, OK, my family’s in North Carolina tonight, people back at the base, your friends, oh my God, what is this going to be? The world’s coming to an end,” he said.

There are no winners in a nuclear war, he said, only survivors.

Benton spent two full days a week for four years in that silo, ready if the president commanded a launch.

For the most part, he said “it was boring, boring and boring,” except for when it was terrifying.

“But I was proud to do that for four years,” he said.