“If they do little or nothing, Floridians will suffer even more than they are now.”

Bob Ritchie, Founder, CEO, American Integrity Insurance Co.

“If Florida is hit with two Cat 4s, it will be the end of Florida.”

Joseph Petrelli, Founder, Ceo / Demotech

Florida Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, calls this “the biggest economic challenge in the state’s history.”

It is. For sure.

Actually, it is more than that, more than the biggest challenge. It is also a crisis. You could accurately call it the biggest economic challenge and crisis in the state’s history.

Florida’s property insurance market — if you can call it a “market” — is collapsing.

“For all intents and purposes, it has essentially already happened,” Brandes contends. “This is what a collapsed insurance market looks like.”

It has been a crisis — at a high, over-the-pot boil — for two years, and a growing boil for the three years before that.

Everyone in and around the industry, including a few legislators intimately familiar with the industry, saw it coming. They warned about it with increasing emphasis in 2019 and 2020, urging legislative leaders and lawmakers to make needed reforms.

In particular, two senators — Brandes and Sen. Jim Boyd, R-Bradenton, an insurance agency owner — tried. Brandes, throughout his four-year term, urging the governor’s staff to act the past three years.

In 2021, Boyd sponsored SB 76, proposing sweeping changes; and this past session, he tried again with SB 1728.

And yet, in the two years of his speakership, Florida Speaker Chris Sprowls, R-Palm Harbor, single-handedly resisted and rejected every meaningful change that the Senate and House members have proposed.

One insurance executive bluntly stated Sprowls “eviscerated” key provisions from SB 76. And this past session, even knowing how bad the crisis was growing, the crisis worsened as a result of Sprowls doing nothing.

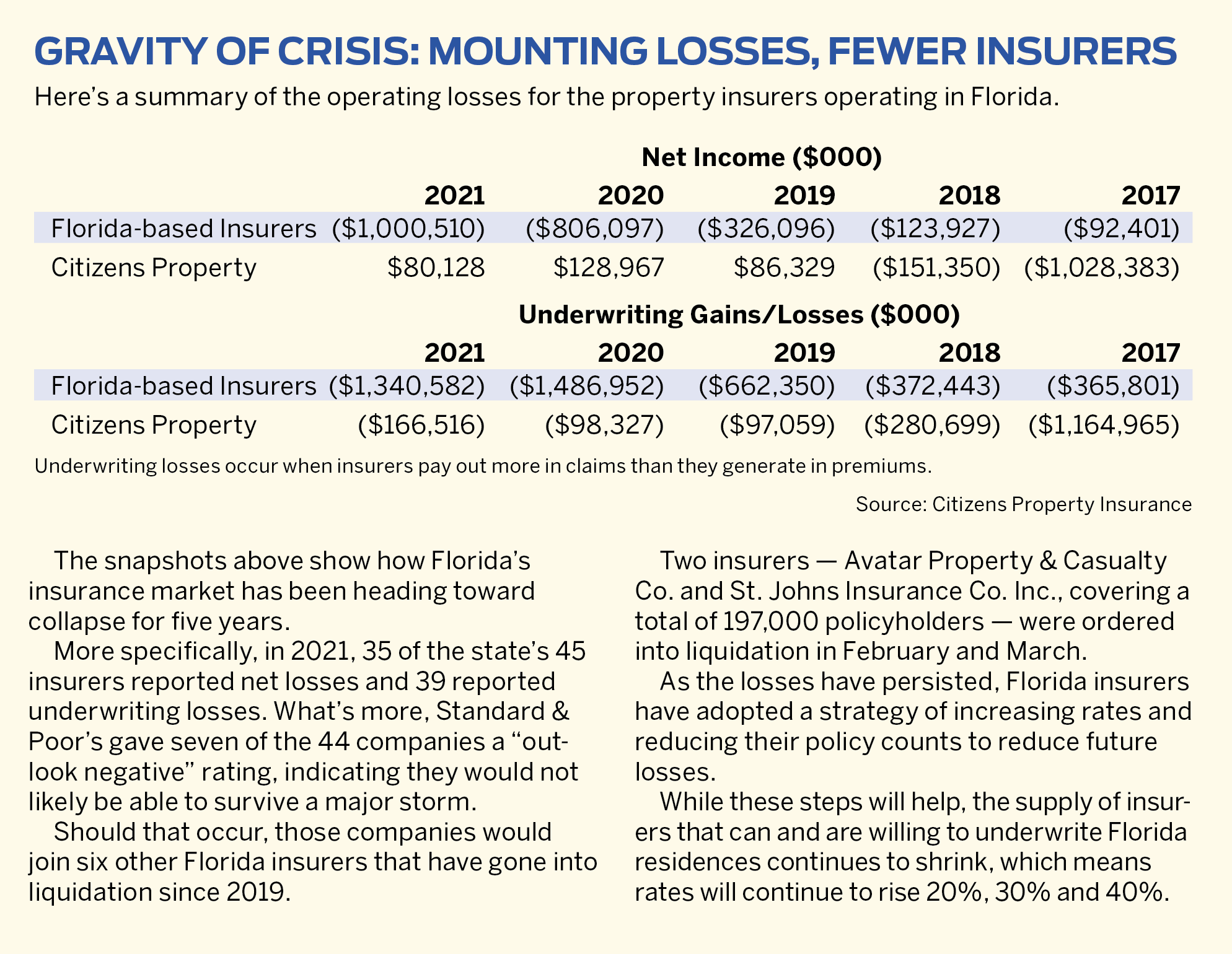

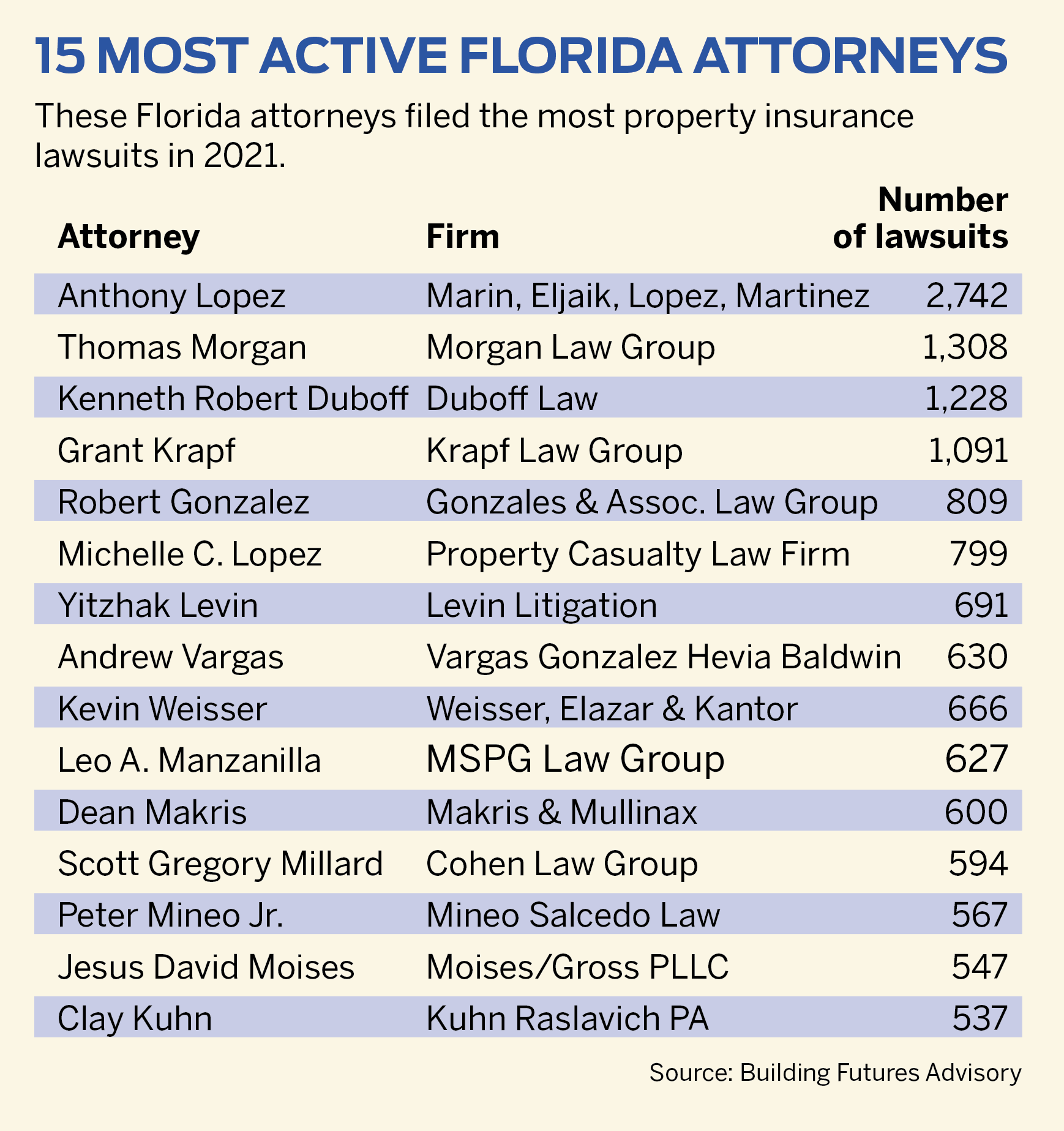

To wit: Much has been written about Florida having 79% of the damage-claim lawsuits nationally while having only 9% of the damage claims, and that while insurers have paid out $15 billion to cover claims since 2013, 71% of that money has gone to plaintiff attorney fees and only 8% to property owners.

Everyone involved, including Sprowls, has known this flood of lawsuits is the crux of the problem. And yet, in 2021, the number of damage-claim lawsuits filed topped a record 100,000. So far in 2022, conditions are worsening. Lawsuits rose 30% in January and 17% in February compared to those months the previous year.

After having immersed himself fighting the coronavirus and the culture wars the past two years and in early 2022, and after the failure of the Legislature to act this spring, Gov. Ron DeSantis realized the insurance crisis needed to be addressed — now. He knows his political future is at stake.

Beginning May 23, the Legislature will convene a special session to begin trying to save an industry that is the backbone of Florida’s economy.

Without affordable property insurance, it’s no exaggeration to say Florida real estate will collapse and the Florida economy will go into another Great Recession — even worse if the unthinkable occurs: direct hurricane hits.

There will be excruciating economic pain — on top of the inflation already ravaging average Floridians.

In this special report, our hope is to give you, our readers (and all Floridians) the perspective and information you need to call your legislator and demand action.

We will explain:

• The gravity of the crisis.

• Why the crisis exists — who and what caused it; what’s making it worse.

• How bad it really is.

• What is ahead for Floridians if it isn’t fixed.

• The politics influencing it.

• What should happen in the special session.

• What is likely to happen.

“I have a bad feeling about 2022,” says Joseph Petrelli, CEO and founder of Demotech. His company has been rating and evaluating the financial health of Florida’s property insurers since 1996.

“If two Category 4 hurricanes hit Florida this year, it’s the end of the world in Florida,” he says.

Petrelli isn’t just talking about the physical destruction that two major hurricanes would inflict. He’s referring as well to a catastrophic insurance and rebuilding aftermath.

If the Legislature fails to enact bold reforms to property insurance statutes in its special session, Petrelli sees three more catastrophes that would be as big or bigger than the property damage from two Category 4 hurricanes:

• The number of damage-claim lawsuits in the two subsequent years would so overwhelm the state’s courts that “claims would not get settled,” Petrelli predicts. They would become backlogged in the courts the way the foreclosure suits were backlogged for three years in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession.

• The cost of materials and supplies to rebuild would skyrocket because of existing shortages and backlogs.

• Existing labor shortages would drag out repairs for years.

“There’s nobody to fix things,” Petrelli says.

Assessments & exorbitant rates

Most Floridians likely are unaware they have a financial stake in Citizens Property Insurance Corp., the state-owned, taxpayer-owned property insurer of last resort.

When Floridians are unable to find insurance from a private carrier, or if the cost of that insurance is too high, they can find refuge in Citizens.

Not only is Citizens there as a last resort, its premiums are the lowest in the state.

In today’s collapsing market, Citizens’ policyholder rolls are skyrocketing as most Florida insurance carriers are shedding or not renewing policies to try to stay solvent.

Citizens is adding about 32,000 new policies a month to its rolls. It is growing so quickly that it is on the verge of a 100% increase in policies from February 2021 to year-end 2022 — from 552,000 to 1,064,000.

This is bad news for Floridians.

As the state-owned insurer, the Legislature in 2002 gave Citizens the authority to impose assessments to cover its losses in the event of major catastrophes.

If a major hurricane hits South Florida, which includes 50% of Citizens’ policyholders, and the damage is so great that it exhausts its reserves, reinsurance and money from the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, Citizens can impose surcharges on its policyholders and assessments on all insurance companies doing business in the state.

And that means those insurers would pass on those assessments to their policyholders — on top of the already exorbitant insurance premiums policyholders are paying.

Although unlikely, Citizens has the legal authority to impose assessments up to 45% of policyholders’ existing annual premiums.

In a presentation to the Citizens board last month, company CEO Barry Gilway showed the potential impact of 1 million-plus policyholders and two Category 4 storms. If one storm took the pre-landfall potential path of Hurricane Irma in 2017 up the west coast of Florida and the other took the actual path of the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, the assessment on Floridians would total $14.5 billion.

The more policies Citizens takes on, the greater the potential assessments in the event of disasters.

This points to another reason state lawmakers would want to adopt remedies to create an environment where private insurers can thrive — and to avoid taxing Floridians even more.

“This is a whole new package of stupid”

Policyholders are well aware of the 20%, 30%, 40% and 50% increases in their premiums. But if you owned and operated an insurance agency in Florida the past two years, it has been a living hell.

Michael Mailliard, owner of MIC Insurance on Longboat Key, says when he tells his clients about their rate increases, or worse, their policies not being renewed, the initial response typically is “WTF!?”

“I’m having to educate them on why they need to replace their roof when it has five years of life left on it,” he says. “I have to be a hard guy and persuade them to replace their roofs if they want to maintain their insurance.”

Mailliard says he knows of only two carriers that will insure roofs up to 30 years. That’s what it used to be. Some are down to 20 years; some 15; some only 10; and some, he says, will insure only new roofs.

But even when he persuades clients to replace their roofs, to make matters worse, it’s now taking eight to 10 months for the materials to show up.

“Nobody in anybody’s career in this business has seen anything like this,” Mailliard says “This is a whole new package of stupid.”

Multiply that by the 66,200 Floridians who work in Florida’s insurance agencies.

It’s not any one thing. It’s a lot of things. But some things and some people are more responsible than others. Here are major contributors:

• The Florida Supreme Court’s 2017 Joyce decision:

In 2017, the Florida Supreme Court rejected long-standing legal precedent and practices regarding the awarding of legal fees known as contingency fee multipliers.

Before the Joyce decision, the courts awarded multipliers of 1.5 to 3 times the fees on top of normally accepted contingency fees in “rare and exceptional” cases and when there was “competent, substantial evidence” justifying the multiplier.

In Joyce v. Federated National Insurance Co., Charlie Crist-appointed Supreme Court justices threw out rare and exceptional and ruled that fee multipliers could be applied in almost any case.

This has been the mother lode for plaintiff lawyers.

• Flawed incentives lawmakers voted into state statutes: In Universal Insurance Holding’s 10-Q report, the company’s management explains the consequences of Florida statutes that codify “one-way attorney fees” in property insurance cases:

“The one-way right to attorneys’ fees essentially means that unless an insurer’s position is entirely upheld in litigation, the insurer must pay the plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees in addition to its own defense costs. This affects not only claims that are litigated to resolution, but also the settlement discussions that take place with nearly all litigated claims.

“The one-way right to attorney fees creates a nearly risk-free environment, and incentive, for attorneys to pursue litigation against insurers.”

The oft-repeated statistic explicitly illustrates how out of whack the incentives are: Florida has 79% of the national property damage-claim lawsuits, but only 9% of the national damage claims.

• Plaintiff lawyers exploiting incentives: Guy Fraker, founder of Building Futures Advisory, has conducted extensive research the past three years on what he calls the state’s “litigation economy.” His research reveals 80 to 120 law firms, contractors and public adjusters working as teams, converting $4.8 billion a year in premiums paid by Floridians into their own revenue stream. (See box.)

Says Bob Ritchie, CEO of American Integrity Insurance Co.: “This is a man-made crisis. Why in the world would we let 2% of the populace exploit the rest?”

• Unscrupulous roofers and contractors: The wife of a Sarasota insurance agency owner, who asked not to be identified, tells this story:

While checking out at a gift shop, she struck up a conversation with the checkout associate. They began talking about their husbands’ jobs. The checkout associate said she and her husband had recently moved to Florida. He’s a roofer.

The store associate said he interviewed at five roofing companies and at each one his interviewers asked if he would be willing to inflict damage on roofs when conducting inspections.

He said no. None of the firms would hire him.

This is not an isolated case. Nor is it to say all contractors and roofers are unscrupulous and unethical. But it’s real and another illustration of how incentives influence behavior and consequences.

As is, Florida’s building codes provide incentives for roofers to find and create damage. State codes require that if 25% of a roof is damaged in an event, the entire roof must be replaced.

• Use of AI and social media to fuel lawsuits: Like most businesses these days, plaintiff law firms, contractors and roofers focusing on property-damage claims and roof replacement are becoming sophisticated users of geo-targeting and the use of keywords on internet search engines to drive potential clients to them.

And it’s working. Once a law firm or a public adjuster secures a client who has roof damage, it’s easy to take his address and comb his neighborhood.

Fraker contends the use of AI has become more sophisticated than that.

His data “strongly suggests specific insurers are targeted with an explicit purpose determined by an overall litigation growth strategy. The common attribute shared by all target insurers is premium growth and surplus volume by market share.”

• No. 1 reason for the why — Speaker Chris Sprowls: Every legislator in Tallahassee knows that Sprowls, a lawyer, has blocked meaningful insurance reform the past two years in ways that benefit the trial Bar.

In 2020, he ordered the deletion of all proposed roof repair reforms the Senate passed in SB 76. In 2021, Sprowls did not even allow the House to consider another insurance reform bill the Senate approved, SB 1728.

Sprowls did not return phone calls or emails seeking his response and comment.

Often in the Legislature, to little surprise, what is or isn’t addressed has little to do with good public policy. What matters is how it affects politicians’ careers and reelection.

The special session next week is full of that political intrigue.

At the top: Gov. DeSantis has a lot of motivation to pursue meaningful insurance reform. One of his Democratic opponents for his reelection bid, former Gov. Crist, is campaigning that the failure of DeSantis and the Republican Legislature is the reason the state’s insurance industry is collapsing.

Crafty politician that he is, Crist is telling listeners that under DeSantis insurance premiums have tripled from when he was governor — neglecting to tell voters, of course, how his policies chased the national insurance companies out of Florida and created an insurance crisis that planted the seeds for what exists today.

Meanwhile, in the Senate and House, President Wilton Simpson and Speaker Sprowls are at the end of their leadership terms.

They no longer have carrots and sticks to force lawmakers to vote certain ways. They can no longer punish legislators who don’t go along with them or reward those who do.

DeSantis has this: He has yet to sign the state budget into law.

If lawmakers go against him in the special session, he can veto the special projects and funding for their districts.

The legislative leaders who have ascending power are incoming Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, R-Naples, and Speaker Paul Renner, R-Palm Coast.

In the Senate, Simpson has given his confidence to Sen. Boyd to help craft whatever legislation comes before the Senate. In the House, Sprowls alone is in control of what the House will propose or consider.

Insurance executives and lawmakers we interviewed agree: If the special session is to result in meaningful, bold reforms, DeSantis will need to sway Sprowls to go along.

But Sprowls will be conflicted.

He has been a friend of the trial Bar, the largest campaign contributors in the state. The talk in Tallahassee is Sprowls is eyeing a run for attorney general.

The question for Sprowls will be this: What’s more important … the millions of trial Bar money to help his political ambitions or Floridians’ insurance premiums?

Politically, this special session will be a duel: DeSantis versus Sprowls and the plaintiff attorneys.

Ritchie calls Florida’s insurance crisis a man-made crisis. It has little to do with natural disasters.

It’s obvious, then, the No. 1 problem to solve is to dramatically reduce fraudulent claims and lawsuits.

“Shut the door on the core motivators for bad actors,” Fraker says.

Ritchie is advocating for two essential reforms — lawyer fees and how roof payouts are calculated.

He wants to revert to the contingency fee multiplier system for legal fees — “rare and exceptional” — that existed from 1992 until the Joyce decision in 2017.

“That worked,” he says.

Another option others favor: Eliminate one-way attorney fees and instead adopt a system in which the state plays no role in attorney fees. Each side pays its own fees. As current law exists, plaintiff lawyers always win; they get paid by insurers whether they win or lose.

Roof reform: Ritchie advocates a set formula for valuing roofs that need repair.

Essentially, a meaningful reform would be to treat the insurance of roofs the way auto damage is treated.

When you total your 2010 Ford, your insurer doesn’t give you a check to buy a new car; the check is for the depreciated value of the car, or actual cash value.

In Florida, the only state that does this, if 25% of your roof is damaged in an event, state building codes require the entire roof must be replaced. All other states put the threshold at 50%.

At the least, a simple and quick way to address the crisis would be for Boyd to reintroduce SB 1728, the bill Sprowls ignored.

That would be a big step toward the goal Brandes and Boyd have pursued for the past two years — a first step toward establishing a rational, stable, competitive property insurance market and, in the process, saving Florida’s economy.

As this was published, neither the Senate nor House bills to be considered had been filed.

For nearly the past month, DeSantis, his staff, Boyd and the staff of the Senate Banking and Insurance Committee; Speaker Sprowls and his staff; and Rep. Jay Trumbull, R-Panama City, have been negotiating.

Prediction: Based on multiple interviews with lawmakers and insurance insiders, expectations are not high for dramatically positive reforms.

Ritchie is in that camp.

“We’ll get through this crisis,” he says. “But it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

Earlier this week, Sen. Brandes, the lawmaker who triggered the special session and who has devoted his four-year term to trying to create a stable property insurance market, said he, too, had heard the bills likely to be submitted would be underwhelming.

“If that’s the case,” said Brandes, regarded as the Senate’s maverick of dissent, “I’ll be the first to stand up and say: ‘Why are we here?’”