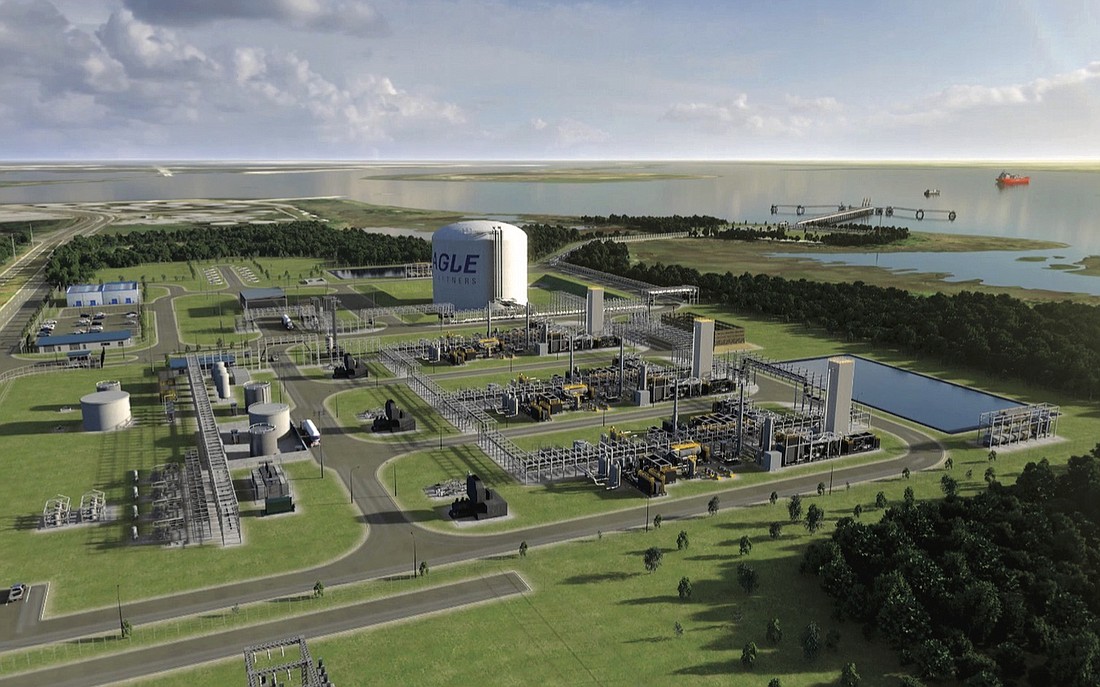

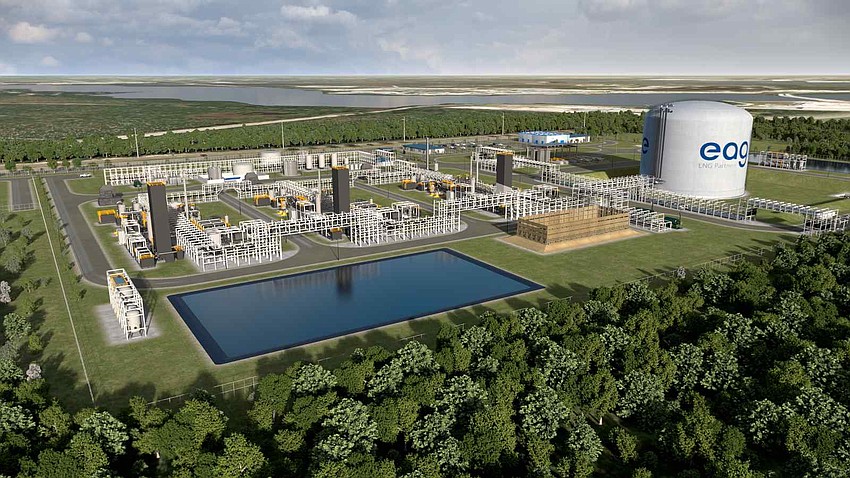

Nearly 3½ years after the Jacksonville City Council approved a development agreement for Houston-based Eagle LNG Partners LLC’s proposed liquefied natural gas export facility in North Jacksonville, the company is working to secure federal regulatory approval to complete construction.

Eagle LNG has been coordinating with the Jacksonville Fire and Rescue Department, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office and the U.S. Coast Guard for a year to complete an Emergency Response Plan required by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, according to company Vice President of Government and Public Affairs Linda Berndt.

“This is the next step toward one of FERC’s construction requirements and is expected to be completed soon,” Berndt said by email May 23.

She said Eagle could not speak for the commission regarding how long that approval will take.

President Sean Lalani said March 27 he hoped for approval and groundbreaking this year on what was pitched in 2019 as a $542 million facility.

Eagle LNG’s Jacksonville expansion plan is a key component of the company’s strategy to export and sell natural gas in a contract with the island nation of Aruba and expand the company’s market reach in the South Caribbean.

Eagle LNG is party to a memorandum of understanding that the Jacksonville Port Authority and Aruba Ports Authority NV signed March 27.

The agreement is meant to “promote business and tourism opportunities between the two regions, share best practices on port operations and environmental sustainability and explore the potential for trade and business development,” JaxPort said in a statement.

Lalani told news reporters after the signing that Eagle LNG has been working with Aruba since 2013 on a 20-year agreement to provide the country with natural gas shipped from Jacksonville to the island to replace more expensive heavy fuel oil.

He said Eagle LNG is working through the Aruba government’s permitting process to build a $100 million receiving terminal as part of that deal in conjunction with its Jacksonville expansion.

Eagle LNG also could use the 75-square-mile island off the coast of Venezuela as a point to re-export natural gas and provide market access to other counties in the Southern Caribbean.

“There are also a lot of islands in the Southern Caribbean that are smaller than Aruba where an investment the size that we’re making in Aruba won’t make as much sense,” Lalani said March 27.

“So what the terminal in Aruba allows us to do is then re-export that LNG (liquefied natural gas) to some of those smaller islands that are currently burning heavy fuel oil or diesel and want to move to a more stable, more secure, cleaner-burning source like natural gas and that allows us to potentially introduce hydrogen into that mix,” he said.

Jacksonville’s position

Progress on Eagle LNG’s export facility planned on 200 acres at 1632 Zoo Parkway along the St. Johns River was slowed by the coronavirus pandemic and the cost could be rising.

In May 2022, Eagle LNG began preliminary work on landscaping and the relocation of protected tortoise species at the site.

In her email, Berndt did not confirm the a higher price, but said Eagle LNG “will be in a position in the near future to update on total installed capital cost.”

“As with others, Eagle LNG is not immune to macroeconomic forces that are impacting industries throughout the country,” she said.

According to Berndt, “it’s too early to answer” whether Eagle LNG will ask the city to raise the property tax payout cap in its incentive deal for the project and company representatives have not discussed the issue with the city.

In December 2019, Council awarded a Recapture Enhanced Value Grant to refund 50% of the incremental increase in ad valorem taxes for 10 years capped at $23 million.

Council approved a one-year performance extension to the deal in May 2021 to give Eagle LNG more time to start construction.

In the meantime, Eagle LNG has expanded its existing Maxville facility, which the company says can now produce more than 200,000 gallons of LNG per day.

The city approved a permit in January for a 115,000 GPD capacity liquefaction system installation at $8.27 million for the Maxville site in West Jacksonville.

The majority of the LNG produced in Maxville moves through Eagle LNG’s Talleyrand LNG Bunker Station at JaxPort for bunkering of Crowley’s CON-RO Puerto Rico trade routes, bunkering foreign-flagged ships powered by LNG, or is shipped in containers for power generation in the Caribbean, Berndt said.

LNG in the Caribbean

In 2020, Lalani said Eagle LNG was prepared to spend $1 billion to invest in its Caribbean market. “That number is quickly being eclipsed as new Caribbean countries commit to LNG for power generation,” Berndt said May 23.

Ted Kury, director of Energy Studies for the Public Utility Research Center at the University of Florida, works with utility regulators in the Caribbean, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Pacific islands on executive education.

He said May 18 that Caribbean nations have historically relied on heavy fuel oil, diesel and propane for power. That’s expensive, but he said the island nations were too small to build 400- to 500-megawatt coal-fired power plants when peak needs of these countries are typically 40 to 50 megawatts.

According to Kury, the U.S. pays 9 to 11 cents per kilowatt hour while electricity in smaller Caribbean nations can be 40 cents per kilowatt hour to produce.

“You have much higher electricity prices due to this imported oil and you’re seeing a lot more of these islands that are looking for alternatives,” Kury said.

According to Kury, Jamaica was the first Caribbean nation to successfully add natural gas into its energy mix about 15 years ago, allowing the country to retire older and less efficient heavy oil plants.

Kury said he would have expected all the Dutch Caribbean islands, including Aruba, to lock into natural gas deals in Trinidad or Venezuela, which are geographically closer than the U.S.

According to Kury, the Aruba contract will make Eagle LNG “competitive with anybody” trying to tap the Southern Caribbean energy market.

“In the context of the Caribbean, I think the fact that they’re able to sign an agreement with Aruba means that they are probably in play for any island that chooses natural gas as an alternative,” Kury said.

In April, Eagle LNG announced it signed an agreement with Aqualectra NV, the electric and water utility in Curacao, to negotiate providing the country with natural gas.

“Aruba was kind of the first domino to fall, and at that point, all of the islands are moving over from dirty, expensive heavy fuel oil over to clean burning natural gas from Jacksonville,” Lalani said.

Aruba Prime Minister Evelyn Wever-Croes said March 27 at the JaxPort signing that Eagle LNG would be providing transition fuel until the country can produce more solar and wind energy.

She said the country of about 120,000 people is working to diversify its economy, which mainly relies on tourism and trade partners.

She said political tensions in Venezuela caused Aruba to close its borders to the South American country, although it has received 17,000 to 18,000 refugees.

The memorandum at JaxPort was also signed by Lalani, JaxPort CEO Eric Green, port board member Wendy Hamilton, Vice Chair Daniel Bean and Florida CFO Jimmy Patronis.

The UF center director said LNG is one of many alternative fuels being explored in the Caribbean. Others include geothermal power, wind, solar and small-scale, modular nuclear reactors.

Kury said some Caribbean countries have broader policy goals to move away from fuel oil and diesel to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, but others are about cost and energy security.

It is U.S. policy to have excess fuel supply available for at least 15% more generation capacity than needed to be ready for any event that impacts the supply chain, according to Kury.

For Caribbean islands, that need is 30% to 40% more.

“Security of supply is always a critical issue in the Caribbean,” Kury said.

“Because if you can’t generate power with what you’ve got on the island, there isn’t a quick fix. You’re stuck. You have to rely on yourself. So I can certainly understand the argument that security of supply is a big issue for them.”