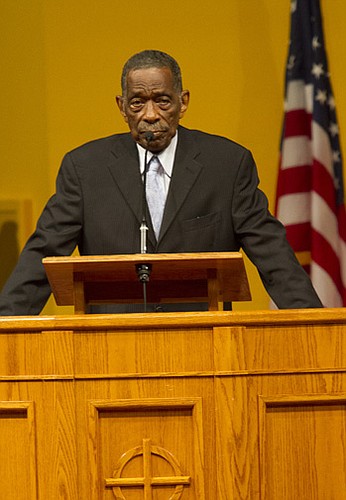

For 47 years of Sundays, Bishop Rudolph McKissick Sr. has been on the pulpit at Bethel Baptist Institutional Church, looking over the congregation he has led.

Even as his son took over regular preaching duties several years ago, McKissick still took his rightful seat at the front of the church.

This Sunday, McKissick will preach his final sermon as pastor at Bethel, leaving a legacy as a powerful force inside the church and across the city where he was born.

"I thought at (age) 86, this was not my generation to pastor," McKissick said of his decision to retire. "That's not a deficiency. That's just acknowledging what is needed today."

That doesn't mean adjusting to his new role will be easy.

"I think I can be a good student and sit and learn, but I can still miss the fact that I'm not teaching and preaching," he said.

Bethel is the only church McKissick has ever known. He grew up in the church, where his father was a deacon. For the 13 years McKissick was a mail carrier, he held several leadership roles at Bethel. When he got the call to pastor there, he left his postal job and put his full might into building the church.

McKissick said he has seen Bethel grow from 500 members to 12,000. It's also become one of the most powerful African-American churches in the state.

Along the way, McKissick became an important leader for all of Jacksonville and a trusted adviser for the city's officials.

From church walls to City Hall

When John Peyton was elected mayor in 2003, he sought out McKissick just like every mayor since consolidation had done.

But Peyton did so with two strikes against him.

He had beaten Nat Glover, an immensely popular African-American sheriff who McKissick supported in the race against Peyton.

Two years earlier, as McKissick watched from the front row, Peyton was among the board members who voted against hiring Michael Blaylock for the job as head of the Jacksonville Transportation Authority. Blaylock is an African-American who Peyton said McKissick had practically raised as a son.

"When I called to make an appointment with him, I was probably the last person in the city he wanted to see," Peyton recalled.

What happened next was a surprise: The two men developed a special friendship that few people knew existed, but both have considered a blessing.

"God was not going to let us separate on those differences," McKissick said. "If anything, they brought us together."

Peyton said he often called on McKissick during his time at City Hall.

"Sometimes we'd talk about public policy, sometimes we'd talk about family and sometimes we'd talk about faith," Peyton said. "He had tremendous insight and perspective."

When Peyton announced Jacksonville Journey, an anti-crime program that was a cornerstone of his administration, McKissick was at his side.

"I considered him to be a partner in making Jacksonville better," he said.

Mayor Alvin Brown said he sought McKissick's advice when running for office and on issues such as jobs and education since he was elected in 2011. He called the bishop "a treasure."

"I consider him as someone who has changed a generation and I'm one of those individuals who he has changed," Brown said. "He's the next thing to God and that's how I view him."

Balancing the message on crime

Mayors weren't the only public official to receive McKissick's counsel. Sheriff John Rutherford said he's often relied on McKissick since he was elected in 2003.

He said McKissick was a great source of advice on not only crime issues in the community but with public outreach programs the the sheriff wanted to do.

McKissick often counseled Rutherford on the importance of balancing the message his office was sending to the community.

"He'd say, 'Look John, people have to know you're not just after the bad guys but that you're wanting to help the good folks,'" Rutherford said.

And when the sheriff wanted to have the Fugitive Faith Surrender program in Jacksonville, McKissick was one of the first people he reached out to.

The program allowed fugitives with warrants for nonviolent crimes to turn themselves in and appear before a judge at a church. If the case was not settled that day, the offender went to court later.

"We had great success with that," the sheriff said.

Though McKissick is leaving his role as pastor, Rutherford will still seek his advice.

"The best part is, I know he'll be there for me," he said.

Son follows path, but on his own

Perhaps the person most affected by McKissick's retirement is his son, his namesake, who will soon be on the pulpit without his father.

Bishop Rudolph McKissick Jr. has known since 2012 that his father was going to be leaving.

"I had just kind of convinced myself that my dad was not going to retire," he said. "I desperately wanted him to. … I want him and my mom to enjoy each other in the sunset of life."

The younger McKissick didn't start out with plans to be a pastor. He originally was an opera major at Florida State University. When he decided to go into music ministry, he transferred to Jacksonville University for its sacred music program.

McKissick Sr. was happy with his son's decisions.

"When he called and said he wanted to get into sacred music, I thought that would be a great thing," he said. "Then he said, 'I could come back and work at the church,' and I thought that would be great."

But McKissick Jr. had one more career decision to share. He was at home, called his father into his bedroom and told him: "The Lord has called me to preach."

His father's reaction?

"He looked at me and walked out of the room. He didn't talk to me," McKissick Jr. said.

Instead, he wanted his best friend to talk to his son.

"Inside he was very grateful and very thankful," McKissick Jr. said. "But he tempered it because he wanted to make sure it was God and not him" who led his son to become a pastor.

One final message

McKissick Sr. has started writing his final sermon as pastor of Bethel Baptist.

"The theme is really to give the best that you have, and the premise of that is love," he said.

That love is necessary to bring the city together, he said, something McKissick has worked toward for decades. It's why he's made himself available to mayors, sheriffs and other public officials.

He believes the relationship between the African-American community and the white community has improved greatly during his lifetime.

But until "we give our best to one another and until we get to loving one another as the word of a good God says," he said, the gap between the communities won't truly be bridged.

Retirement doesn't mean he doesn't still want to help the city.

"I am retiring from pastoring but not from ministry. I'm still a preacher. I can still minister to people," he said.

How will he do that? "That's the big question," he said. "I don't want to interfere with anything about Bethel but I do want to reach out."

He's also not sure what that first Sunday of not sharing the pulpit with his son will be like. How it will feel to sit in the audience, with his back to the parishioners he's led most of his life.

For them, it will be the same. They'll still be behind him.

@editormarilyn

(904) 356-2466