When statewide prosecutor Nick Cox took over the Allied Veterans of the World case, he intended for Nelson Cuba to go jail.

And he knew a lot of people in Duval County wanted that to happen.

Cuba was a veteran cop, the longtime head of Jacksonville’s Fraternal Order of Police. Cox was well aware of Cuba’s reputation as a bombastic union leader, never one to shy away from a public fight or a television camera.

“I knew we were not dealing with a character who was beloved in Jacksonville,” said Cox, who also knew Cuba through a criminal justice training commission.

Cuba was among the handful of the 57 defendants Cox said he concentrated on in the $300 million gambling and money laundering investigation unveiled nearly two years ago.

Kelly Mathis, the Jacksonville attorney for Allied Veterans, was at the top of the list, followed by Cuba and Robbie Freitas, the FOP vice president and a partner with Cuba and others in several Internet cafes.

Last month, Cuba ended his holdout as the last of the defendants with an open case when he pleaded guilty to three charges. He received house arrest and probation.

Cuba was a changed man, Cox said. A broken man.

That led Cox to change his mind about the need for the former police officer to serve time in jail.

Cox realizes some people won’t understand that decision.

But, he said, “I was prosecuting him for Allied, not for being a jerk for 20 years in Jacksonville.”

How it unfolded

Cox said the Allied Veterans investigation had been underway for some time before he got involved. Prosecutors and sheriffs in several counties had been working with the U.S. Attorney’s Office when federal officials decided the case should be spearheaded by the state.

By this point, Cox said, officials were ready to make dozens of arrests. But he delayed that for a couple of months while he became familiar with the details of the massive investigation.

“This was the largest case I ever handled,” said Cox, a veteran homicide prosecutor.

And it was his first gambling case. He pored over cases from the early 1900s when prosecutors were trying to shut down gambling houses in Florida.

In March 2013, nearly 60 arrests were made throughout Florida and in a few other states. Hundreds of millions of dollars in property and cash were seized.

Officials held news conferences in several cities, including Jacksonville, to announce the details of “Operation Reveal the Deal.”

That’s when Sheriff John Rutherford first shared that Cuba and Freitas were caught up in the case.

Rutherford recently said his office was investigating a separate “potential criminal enterprise” when it discovered a link to Cuba and Freitas.

After pulling financial records, he got a call from the Secret Service saying he should talked to Seminole County officials. It turns out Seminole County had pulled the same records.

When Seminole officials asked Rutherford what he was working on, he responded with, “What are you working on?”

The sheriff then learned there was a gambling side of Allied Veterans tied to the money laundering and structuring case his office was working.

That’s when Operation Reveal the Deal was born.

Also caught up in the case was former Lt. Gov. Jennifer Carroll, who was forced to resign by the Governor’s Office the day after she was questioned about her ties to Allied Veterans.

Carroll did work for Allied while serving in the House of Representatives and owned a public relations firm that represented Allied.

When asked about Carroll, Cox paused for a short time as he chose his words. At the time of the arrests, he said, his office wasn’t considering charges against Carroll.

“But I was aware that other agencies were going to continue taking a look at her involvement,” he said.

No charges have been filed against Carroll.

Mathis the top target

From the beginning, Mathis was the top person on Cox’s radar.

The former president of The Jacksonville Bar Association had represented Allied Veterans for years, dating back to the group’s original gaming effort. Those businesses were shut down in 2007 when it was determined they were illegal because they were games of chance, not games of skill.

Allied later turned to sweepstakes through Internet cafes as a way to raise money.

Cox said Mathis presented the sweepstakes as being legal to officials throughout Florida.

“He (Mathis) gave them the wrong information in order to legitimize this,” Cox said.

The prosecutor said Mathis never told his clients the business “could be risky.”

“It doesn’t make them (his clients) innocent,” Cox said. “They relied on his word. He just pushed it right along.”

Mitch Stone, who represents Mathis, has said from the beginning his client was only providing legal advice to Allied Veterans.

He said he thinks prosecutors were swayed by emails they found that referenced few people were using the Internet time being sold as a way for people to play the sweepstakes.

But, Stone said, that’s tantamount to someone buying 10 cases of Pepsi to play its bottle-cap sweepstakes and only being interested in whether the bottle caps were winners versus drinking the cola.

“Have they engaged in gambling?” Stone asked.

Strategies kept changing

Before Mathis’ trial began, Stone challenged the credentials of the state’s expert witness, Robert Sertell, who went undercover in several cafes.

Stone said Sertell never studied the law or the science behind the software in the games.

Instead, Stone said, “He (Sertell) spent five or 10 minutes playing the games and said, ‘that’s gambling.’”

Stone wanted a hearing before a judge on Sertell’s qualifications but before that could happen, Cox decided not to call him as a witness.

Cox discounts there were credibility issues with Sertell. Instead, he said, not calling Sertell and other witnesses was part of a strategy to streamline the case.

“We had been on this for months and were really getting into the weeds,” Cox said. “Sometimes defense attorneys get you in the weeds and try to take you down rabbit holes.”

At that point, he said, his focus became simple: “We have to prove this is a slot machine and the whole case is done.”

Cox said by the time Mathis’ trial started, prosecutors had “flipped” Jerry Bass and Johnny Duncan of Allied Veterans and Chase Burns, who designed the software. He intended to have them testify, he said, but decided otherwise during the trial.

“I’ve never had a case where so many strategy decisions were made on the fly,” he said.

Mathis was convicted by a jury on more than 100 charges and sentenced to six years in prison. He is free while the case is being appealed. Stone said it will be months before the appeal is heard but he is hopeful that key evidence his team was not allowed to use in the first trial will be permitted in a second trial.

If there is a second trial, Mathis will testify on his behalf, Stone said.

“We had planned on putting him on from Day One,” Stone said.

But ultimately the defense felt Mathis’ voice had been heard through many witnesses and they feared it would have extended the trial a couple of weeks with prosecutors possibly using interviews Mathis did with the press and taking them out of context.

Mathis faces being disbarred because of the convictions. A spokeswoman for The Florida Bar said at Mathis’ request, the process to disbar him was placed on hold until the appeal is settled.

‘It was wearing on him’

Cox said after Mathis’ conviction, “a lot of people began to talk.”

Freitas pleaded guilty and received no jail time or fines, as did others.

Cuba also began talking with prosecutors. Cox said prosecutors did not immediately tell Cuba they would work with him, nor did they indicate they wouldn’t seek jail time.

But as the meetings continued, he and his team saw Cuba appeared warn down.

“Do I need to do a complete beat down?” Cox asked himself.

Ultimately, the sides agreed to a deal where Cuba pleaded guilty to three counts, including two felonies. He received a year’s house arrest and four years of probation, plus he paid $115,000 in fines.

Cox said Cuba and Freitas didn’t steal anything, nor were they “on the take.”

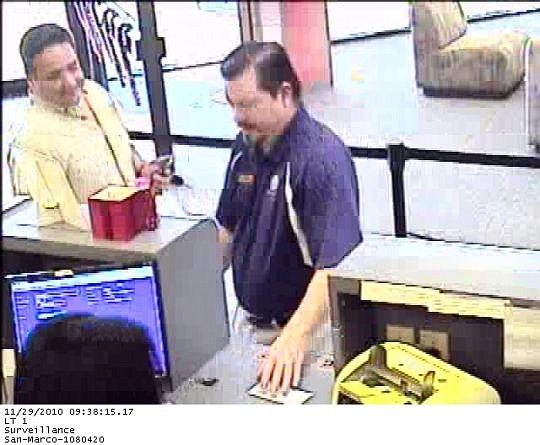

Court records show the two police officers deposited $576,100 from Sept. 4, 2009-Dec. 30, 2011, followed by $571,400 in withdrawals.

Each of the withdrawals was below the $10,000 threshold that could trigger scrutiny from federal oversight agencies.

Rutherford is among those who would have liked to have seen Cuba and Freitas serve a year in jail because police officers are held to a higher standard.

The sheriff said he believes Cuba got Freitas involved in the illegal activity and that Freitas did it because he got into financial trouble.

Rutherford said eight to 10 months into his department’s investigation, he noticed a change in Cuba. He was more stressed, he put on weight and was much more emotionally sensitive, the sheriff said.

“It was wearing on him,” he said.

Rutherford said he thinks Cuba knew he was going to eventually get caught. That’s what police officers believe, he said.

“Living that life where you’re looking over your shoulder, I suspect is not pleasant for anybody,” Rutherford said. “It’s probably even worse for a policeman.”

With the exception of Mathis’ appeal, the cases have all been settled. Only he faces jail time. Most defendants had most or all charges dropped and received all or most of their property that was seized.

Cox had nothing to do with the property being returned. Those issues were litigated separately.

“I was uncomfortable talking about someone’s liberty and their money in the same sentence,” he said.

But, not any more.

Cox said the case changed his mind about tying the two together.

“Jail scares people, but taking their money scares them more,” he said. “I have become a believer.”

@editormarilyn

(904) 356-2466