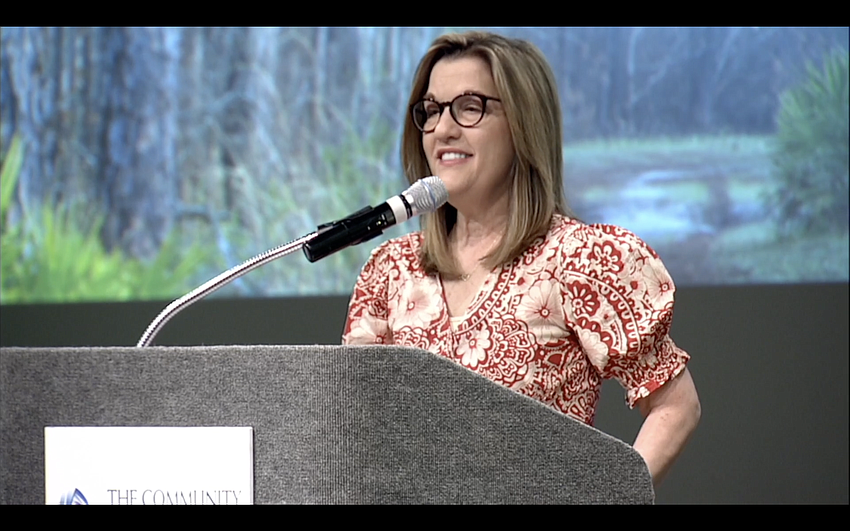

When Nina Waters steps down July 28 as president of The Community Foundation for Northeast Florida, she says she will be able to look back with pride at her work at the philanthropy, where she spent the past 22 years.

The numbers alone reflect her achievements.

• During her leadership, foundation assets have grown from less than $60 million to $630 million.

• The organization grew from being the fifth-largest community foundation in Florida in total assets to the largest.

• Nationally, the foundation rose from 86th largest in 2001 in asset size to 50th by 2020.

A story Waters tells telegraphs her belief in the vision and effectiveness of the foundation.

About 15 years ago, she spoke to a group of local philanthropists about a foundation initiative for education.

After she finished, a member of the group approached Waters and said, “Well, what exactly do you do?”

“I said, ‘Well, I work with The Community Foundation, and we work with donors to help them deploy their philanthropic giving, and so we connect donors to causes that they care about,’” Waters said.

“And he said, ‘Well, in other words, you give away other people’s money.’ And I said, ‘Yes, we do, and I think we do it really well.’”

Established in 1964, the foundation serves Baker, Clay, Duval, Nassau, Putnam and St. Johns counties.

The organization manages more than 600 charitable funds. Waters, who succeeded Andy Bell in 2005, is its second president.

The scope of programs and initiatives created under her leadership extends to public education reform, aging adults, the LGBTQ community, disaster relief, neighborhood revitalization, the arts and more.

Waters, 64, told the nonprofit’s board of trustees in September 2022 that she planned to retire Sept. 1, 2023.

Her successor, Isaiah M. Oliver, who led the community foundation in Flint, Michigan, will step into his new role Aug. 1, and Waters will remain available to him for guidance through the end of August.

The decision to retire wasn’t easy, Waters said in a recent interview at the foundation’s headquarters in the Raymond James Building at 245 Riverside Ave. in Brooklyn, where she talked about her years in the nonprofit sector.

Yet she has no doubt the timing is right.

“I know when I have contributed as much as I can possibly contribute. And I know when it’s time for a new leader to come in to The Community Foundation,” she said. “I have used everything in my bag of tricks.”

The role of president is demanding and time-consuming, she said. Evening and weekend events are common.

“I don’t have the energy that I used to have. Several people have said to me, ‘Slow down a little bit,’ and I’ve said back, ‘This is not a slowdown job.’ It’s not fair to this organization for me to slow down. And I’m not the type of person that can see something that needs to be done and not do it,” Waters said.

The other big factor in her decision is family.

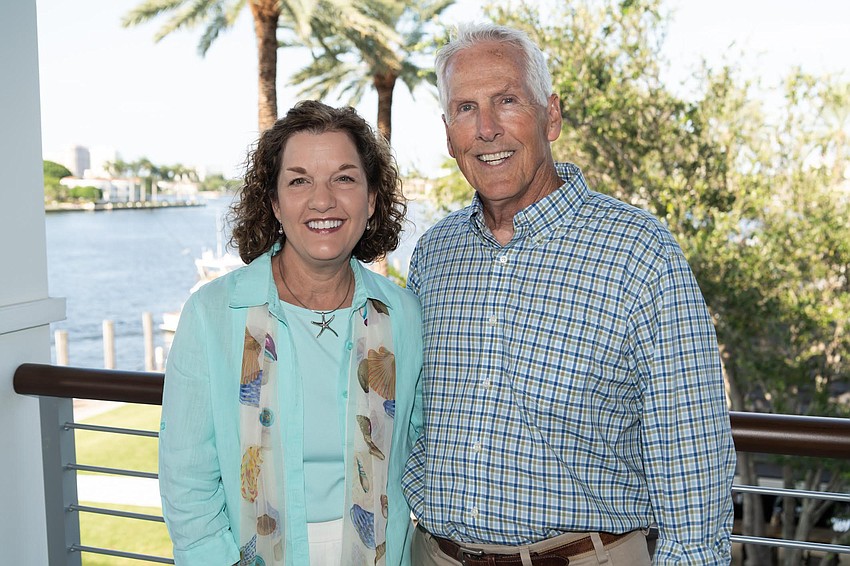

She and Lex Waters, her husband of 43 years, plan to move to Atlanta in September to be near their son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. The discussion to be closer began several years ago. As a result, Nina and Lex now have a house there waiting for them to occupy full-time.

“I think definitely for my family, it will be a good thing,” she said.

She said she looks forward to spending time with - and spoiling - her two grandchildren.

Finding the right path

Waters grew up in Pittsburgh, which she described as “landlocked” and as such, generated her interest in the ocean and marine science.

She had been to the ocean once (in Cape May, New Jersey) when she visited Tampa, then Jacksonville, as a high school senior to look at colleges. Both the University of Tampa and Jacksonville University had marine biology programs.

When she saw the JU campus, she knew that was where she wanted to be, she said.

Waters came from a close-knit Italian family, and her father, who ran a grocery, wanted her back in Pittsburgh. “If you get one ‘C’, you’re coming home,” she said he told her.

She never received a “C” in a class, but the semester-long dissection of a fetal pig changed her academic focus.

Quinton White, her adviser and now executive director of JU’s Marine Science Institute, helped Waters see that other fields — those that involved helping people — could be a more natural fit.

Waters switched to sociology with a concentration in criminal justice. She graduated from JU in 1980 and took a job as an academic instructor at the Jacksonville Marine Institute, which now is AMIkids, a program for at-risk youth.

She met her soon-to-be husband there: Lex Waters, a scuba instructor at the institute.

“We got engaged a month after we met and we got married three months later. It was a whirlwind romance. It was just the right thing, and 43 years later, we’re still married,” she said.

They found that being married and working together could be difficult, and Waters became a vocational coordinator at Jacksonville Job Corps, part of a national youth training program for students ages 16 to 23.

She stayed five years and during that time gave birth to their son, Alex.

By then, Lex Waters was a high school teacher. Hoping to increase their earning potential, she joined the private sector and worked in sales for Mohasco Corp., which owned Cort Furniture Rental Co.

Four years in sales was enough.

“It was the same thing as the fetal pig. There was no intrinsic value in it for me. So I went back into the nonprofit sector, working for the Pace Center for Girls,” she said.

Waters started at Pace in 1989 as program director of the alternative school for at-risk girls, then became executive director.

She was at Pace for 12 years.

“I loved that job, and I loved the team of people I worked with. The challenge for me was, I wasn’t challenged anymore. I wasn’t growing, I was doing the same thing every day,” she said.

“I was feeling like I’ve done as much as I can do, it’s time for someone else to come in with a fresh look and fresh ideas to maybe take it to the next level or to add their own skills and abilities to grow the institution,” she said.

“I had just turned 40 and I thought if I’m going to make a change, this is probably when I need to do that.”

The Community Foundation

Waters put out feelers. Eventually, The Community Foundation approached her about becoming executive vice president.

She turned it down.

“I thought about it for a long time, and I wasn’t sure that it was going to be the right fit for me,” she said.

Her hesitation: “I think I was worried that being removed from the day-to-day good that you’re possibly doing would not be what I wanted. I knew the foundation did good. But you don’t see it and you don’t feel it. That’s the truth.

“I know we do good work. I know our staff does good work. But you are removed from seeing that work. You’re seeing it through others’ eyes. And that’s what I was worried about: I don’t know that I can be this far removed from any good that I’m doing. It’s not really what feeds me. I’m a giver not a receiver. I get joy from giving. I felt like that would be lost.”

Waters changed her mind and took the job after J.F. Bryan, a foundation board member she knew and respected, called her. He said, “I think you’re making a mistake.”

It was late summer in 2001.

In the first two years, there were days when Waters thought she had “made a great landing in the wrong airport.”

“I came from a direct service organization, where there were students around every day, and there’s all kind of fun and excitement and very casual, everyone was on a first-name basis and a lot of noise and confusion all the time,” she said.

At the time, The Community Foundation was in a remodeled attorney’s office in the Atlantic National Bank building at 121 W. Forsyth St. Downtown.

“It was very different. Bow ties, dresses and high heels, and quiet, so quiet,” she said.

“I was trying to find my place, trying to help this organization understand the complexities of the nonprofit sector, trying to put some systems in place, trying to be an advocate,” Waters said.

“And also to learn, because it was a hugely steep learning curve. I remember sitting in my first investment committee meeting and I didn’t even know what a basis point was. I remember going out and getting ‘Investments for Dummies,’ and I was like, ‘I just have to get up to speed.’”

The other challenge was Waters started two weeks before the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The benefits of a thriving economy came to a sudden halt.

“The world stops and the market crashes and the need for nonprofit services goes up and funding goes down. In our sector, when there’s a crisis, demand goes up and funding goes down,” she said.

“Our whole business model had to change because our income to the foundation changed significantly. We had to change with that: laying off staff, trimming down some of our grantmaking initiatives. It was a really hard time. It was very challenging.”

Bell, the foundation president, proved to be an invaluable on-site mentor, Waters said.

When she became president in 2005, she felt she was ready for the job.

“I’m glad that he was here to guide me. The economy improved, I was able to add staff back in, start building a team. Over time, I was able to build my own team of people that are incredibly committed and really work hard,” she said.

“When I left Pace, I never thought I’d have a group of co-workers and teammates like that. I’m so lucky. Some people never have this in their lifetime. I had it, and I never thought I’d get it again,” Waters said.

“And I have it again. It’s just a blessing, because, you know, you’re here more than you’re with your family, so you might as well enjoy it.”

A month after Waters became president, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She said she is a private person who, after discussing the situation with the foundation board, chose to not share the information beyond the staff.

The next five years included surgeries, radiation and medication, and she has been cancer-free since then.

“I’m really lucky,” Waters said. “But it was an interesting way to start a new gig.”

Mentors and success

Waters’ impact on The Community Foundation can also be measured by the funds established during her leadership.

According to timeline information provided by the foundation, the funds include: assisting in establishing the Eartha M.M. White Legacy Fund, Jacksonville’s first major African American philanthropy, in 2005; establishing the Jacksonville Public Education Fund, an independent 501(c)(3) to advocate for high quality public education for all Duval County students, in 2009; launching a $50 million Quality Education for All Fund to provide direct support for excellence in teaching and leadership within Duval County Public Schools in 2013; establishing the LGBTQ Community Fund for Northeast Florida to improve the lives of those in the LGBTQ community in 2014; establishing the A.L. Lewis Black Opportunity & Impact Fund to advance equity and justice in health care, education and economic development through strategic investments in Jacksonville’s Black community in 2022; and raising funds to establish a local chapter of Thrive Scholars, which creates opportunities for high-achieving students of color from low-income families, the first in the Southeast, also in 2022.

In 2012, philanthropist Delores Barr Weaver opened a $50 million Donor Advised Fund, the largest in the foundation’s history, and J. Wayne and Delores Barr Weaver moved the Weaver Family Foundation to The Community Foundation.

Weaver has made more than $180 million in grants to nonprofits through The Community Foundation, including establishing more than $33 million in designated endowments that will provide annual income to nonprofits in perpetuity, the foundation said.

Waters reflects when asked about her effectiveness as a leader.

“I think what helped me is that I had mentors that said, don’t doubt yourself, you can do this and you’ve got this. In times when I was having doubts, or feeling like I just didn’t quite have my feet under me, I would talk to those folks,” she said.

Sherry Magill, who retired as president of the Jacksonville-based Jessie Ball duPont Fund in 2018 after 25 years, was “extremely helpful,” Waters said. “She was a great source of support and advice and a listening ear.

“She also connected me to other leaders in the community foundation sector, and so did Andy (Bell). Building a peer network of community foundation CEOs — I have six of them that I’ve been close to all this time from other communities — that’s been extremely important.

“I would say the best thing that I’ve ever done is building this peer network of people that I trust and that understand our work and that you can jump into a conversation with and they know where you are, and they can give you advice that’s informed.”

Delores Barr Weaver has played a crucial role in her career as well, she said. They met when Waters was at the Pace Center. Weaver was on The Community Foundation board when Waters came to the organization.

“She was ready to rotate off, but she stayed another year, just to make sure that things went well. And she has been there for me all of these years. And that has made a difference because she is probably the most creative and effective philanthropist that I will ever know,” Waters said.

“She’s taught me a lot. She has truly changed philanthropy for Northeast Florida. “

Waters tried to sum up her feelings about her work at The Community Foundation.

“I think the biggest reward for me has been people trusting us with their hopes and dreams. And they do. And letting us into their lives and getting to know what they hope for their children and their grandchildren and their community, and then trusting us to help guide them and provide opportunities for them to make philanthropic investments that are meaningful,” she said.

She added:

“The other thing that I think has been rewarding is there are times that we find an initiative that we feel is important to the community. And we have donors that trust us enough to co-invest with us. We’ve helped to create some really important infrastructure organizations that are really important to the health of our sector.”