As Circuit Judge Lawrence Page Haddock Jr. walked into an elevator at the old courthouse a few years back, he was greeted by a face from the past.

He didn’t recognize the young woman, who was about 25, but immediately remembered her after she introduced herself.

Many years before, he ordered the woman and her brother be pulled from their parents’ home.

The children were malnourished and not always properly sheltered by their young parents who struggled with substance abuse, the judge recalled.

That day in the elevator, Haddock saw the woman had made it out of that terrible situation. She appeared to be a loving, caring mother to two healthy children.

Handling those types of cases was a rewarding assignment, Haddock said, maybe the most rewarding in his nearly 41 years as a judge.

“You literally go home every day feeling you may have saved one or two lives,” he said.

Haddock will soon leave his career as a judge. Not because he wants to retire, but because the Florida Constitution says a judge can’t work after his or her 70th birthday.

The only exception is if that birthday comes after the middle of the term. Haddock missed that threshold by less than two months.

Being a judge is a career he shared with his father. It’s how he met his wife, with whom his first date, of sorts, was shopping for combat boots. And it’s the only job his two children have ever known him to have.

Climbing the Ivy League

Haddock comes from a family of lawyers. In addition to his father, three of Haddock’s cousins and a nephew became attorneys.

So, it was no surprise the law held a fascination for Haddock.

What surprised the Murray Hill kid is the path to becoming a lawyer included attending an Ivy League school. He figured his college career would include playing football at either Vanderbilt or Tulane universities.

But, his mother and a guidance counselor from Robert E. Lee High School had other plans.

As a junior, Haddock scored well on a college proficiency test.

Virgie Cone — whom Haddock called “the grand lady of Lee High School” — and his mother, Jewell, sent off for applications to Harvard and Princeton universities.

One weekend his mother sat him down and said, “You’re filling out these applications.”

Haddock said he didn’t mind doing it, but he also didn’t think anything would come out of it. Plus, he said, “You didn’t argue with my mom very much.”

Both schools accepted Haddock, who chose Harvard.

Haddock’s father told his son not to make his college choice based on any financial decision. It would be a stretch for the family to pay for Harvard, his father said, but it was the opportunity of a lifetime.

“It will change your life,” the elder Haddock told his son.

In many ways it did, including one he would discover decades later when he was appointed to the circuit bench.

Meeting the rich and famous

The first time Haddock saw the Harvard campus in Cambridge, Mass., was when he showed up with his steamer trunk. It also was the first time he flew on an airplane.

He had quite an experience at Harvard.

One of his suite mates was Max Factor III, from the Beverly Hills cosmetics family; he met first lady Jacqueline Kennedy when she attended an event there; and he was playing in a freshman football game against Yale the day President John Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

They announced the president’s death to the crowd at halftime, but didn’t tell the players until the game ended.

“You never heard such silence out of that big of a crowd of people,” he said of the audience during the second-half. “You could tell something was up.”

Haddock majored in American history after 1787. He still loves reading history books, including a couple in his office, plus a growing stack beside his bed.

“It never goes down. It always goes up,” he said.

Making his father proud

After a little under two years in the Navy, Haddock went to law school at the University of Florida. (He retired as a captain in the Navy reserves after 26 years at age 60, which was mandatory retirement age.)

Law school was challenging, Haddock said, and not as paternalistic as college.

“They don’t have counselors or lifestyle coaches,” he said. “It’s ‘here’s the work and if you want to be a lawyer, do the work.’”

Then came The Florida Bar exam. The law firm Haddock was going to work for paid for him to fly to Miami to take the test.

Instead of flying home, he rode back to Jacksonville with three buddies.

“We spent the whole trip coming back from Miami debating what we were going to now that we were pretty certain we weren’t going to be lawyers,” Haddock said, with a laugh.

Waiting for the results was sheer terror, he said. But, they all passed.

Haddock wouldn’t share the names, but said one of the three is a retired district court of appeal judge, another served as Jacksonville’s general counsel and the third become a prominent attorney.

Two or three years into Haddock’s first job at a civil law firm, his father passed away.

He’s happy his father got to see him graduate from law school and become a lawyer.

“He got to see I actually had a job and could pay back some of those loans myself,” Haddock said, with a laugh.

Doing the right thing

Haddock spent a short time as a prosecutor, including working for the revered Ed Austin. He described Austin as a good lawyer, great boss and a natural leader. “I think he was a man of honor more than anything,” he said.

He’s never forgotten how conversations with Austin ended: You know what’s right. Just do it.

“After you talked to Ed, you pretty much did know what was right,” Haddock said.

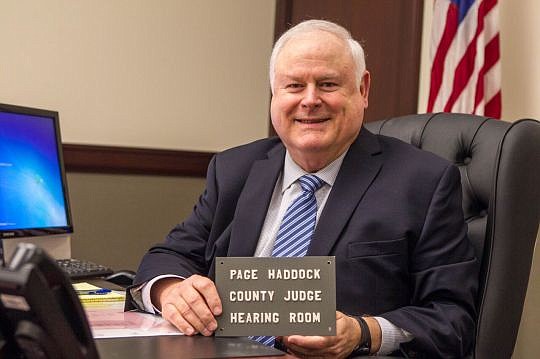

In 1974, Haddock was elected a Duval County judge, like his father who died at age 59 while on the bench.

Instead of having a name plate made for his door, his used the metal plate that hung on his father’s hearing room door. It hung on the son’s door the seven years he was a county judge.

His father had gone by Page, which was the younger Haddock’s grandmother’s maiden name.

Haddock went by Lawrence and sometimes Lawrie, a feminine-sounding nickname he didn’t like.

“I got mail from Wellesley (an all-women’s school), who wanted me to go to college there,” Haddock said.

In December 1981, Haddock was appointed a circuit judge by Gov. Bob Graham. When Graham called Haddock to congratulate him, he praised the judge’s academic credentials of being a Harvard undergraduate and UF law school.

It turns out, Graham had gone to UF undergraduate and Harvard law school.

Haddock realized then his father was right. Going to Harvard really did change his life.

Becoming a judge changed his life in other ways because that’s how he met his wife, Christy.

Combat boots and wedding plans

Haddock had been a judge about four years when he saw a young woman who worked for the public defender’s office walking down the courthouse hallway.

He told himself, “I want to meet that girl,” so he struck up a conversation with her.

She was working for the public defender while waiting to get a spot at the Marine Corps Officer Candidate School.

A couple of weeks later, Haddock said he got a call from Christy asking if he would take her to the Navy Exchange so she could buy combat boots and get them broken in.

“She was so cute and we had so much fun, I asked if she wanted to go to dinner,” Haddock said.

They dated from that time on, deciding to get married in 1990. The wedding was delayed when Christy was deployed with little notice to the Middle East for Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

She was transferred to a sister squadron that needed a female officer, which was deploying in 10 days.

“She called me and said, ‘Cancel the church,’” Haddock said.

Christy was an aviation supply officer, who spent part of the time working out of a ro-ro ship. A Scud missile landed beside the ship, but it was a dud, Haddock said.

They rescheduled the wedding for 1991. Haddock had to do the planning while his wife was going through the process of being discharged from the Marines.

She got home about 10 days before the wedding, he said, in time to “fix all the stuff I messed up.”

Two children but no grandchildren

The Haddocks have two children: Abigail, 23, a marine biologist at the Dolphin Research Center in Grassy Key, and Lawrence Page Haddock III, a 21-year-old senior at Tulane, who will be commissioned in May as a second lieutenant in the Army.

Haddock said he and his wife don’t have grandchildren yet. In fact, he joked, “it looks like our grandchildren may be dolphins.”

They’re adorable and smart, he conceded. “But you can’t snuggle them. That’s the problem,” he said. ”You can’t hold them in your lap.”

His 93-year-old mother is still in good health. About a decade after his father died, she married a man from North Carolina to whom she was introduced by mutual friends.

Ironically, it turned out to be the man she dated her freshman year in college. The man, Bob Blackburn, also was a cousin of the husband of one of Haddock’s fellow former judges, June Blackburn.

Leaving too soon

As Haddock looked back at his four-decades-long career, he counts a couple of the death penalty cases among the most memorable. Coincidentally, they were his first and his last.

The first was Barry Hoffman, who was convicted in the 1980 murder of a drug dealer and the dealer’s girlfriend. The dealer was killed because he stole from the drug ring’s boss and the girlfriend lost her life because she could identify Hoffman and his accomplice.

The last one was Rasheem Dubose, convicted in the 2006 shooting death of DreShawna Davis.

The 8-year-old girl died in a hail of 23 gunshots fired into her grandparents’ home by Dubose and his two brothers, who were retaliating against DreShawna’s uncle.

Despite the heinous circumstances of both crimes, handing down the death penalty is not an easy thing to do.

“When you look another human being in the eye and say, ‘I sentence you to be put to death,’ it’s hard,” Haddock admitted.

“I try to look them in the eye,” he said. “I think I owe them that.”

Haddock feels he’s having to leave the bench at a time he’s better than ever at his job. A good part of that is because experience helps a judge become a better organizer, he said, and it gets easier to make judgments about people’ credibility when they testify.

He’s not sure what he’ll miss the most because being a judge has been what he’s done since he was 28. He doesn’t know what it’s going to be like when he doesn’t spend his days in a courtroom.

Maybe he’ll put a dent in that growing stack of books by his bed.

Maybe he’ll get to hunt and fish during the week now, instead of just on the weekends.

Maybe he and his wife will buy a place in either the Keys or the mountains of western North Carolina.

Either way, it won’t be the same as the career he is leaving much sooner than he wants.

@editormarilyn

(904) 356-2466